In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

At the height of Robert A. Heinlein’s career as a science fiction writer, he wrote a book, Glory Road, which stood out from all his previous work. It was more fantasy than science fiction, with all the trappings and tropes of a fantasy adventure and a heroic quest in a magical world. Wrapped around that exuberant center, however, was a rather downbeat view of life and society, and a deconstruction of some of those familiar fantasy tropes.

I can’t remember exactly when I first read this book. It was sometime in the late 1970s, either late in high school or early in college. The copy I owned was a Berkley Medallion paperback edition, with one of those impressionistic Paul Lehr paintings they used on their Heinlein reprints. While there were parts of the book (especially the non-quest segments) that I didn’t enjoy as much, I read the book a number of times, to the point where it ended up a pile of disconnected pages. And that had me looking for a new copy.

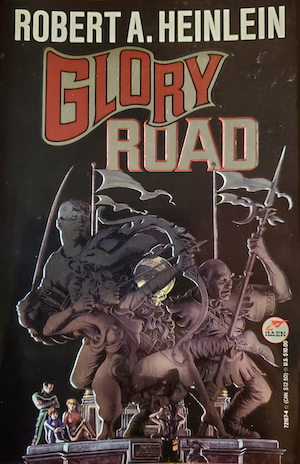

The new edition I found was the Baen 1993 trade paperback edition. The cover is an interesting one, depicting Oscar, Star, and Rufo as a giant metallic heroic sculpture, almost monochrome except for a few tourists standing around the pedestal. Baen, during that era, was partial to the use of metallic inks, satin and gloss finishes, embossing and other effects on their covers, and in this case, it worked quite well. The artist, who was adept at painting metallic subjects, was Stephen Hickman, one of my favorite artists, who sadly passed away in July 2021. Interestingly, I found that I’d never read the new copy after adding it to my shelves, which indicates that my enthusiasm for the book has waned over the years.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) is one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, frequently referred to as “the dean of science fiction.” I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, Have Spacesuit Will Travel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Citizen of the Galaxy, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), as well as The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Red Planet.

The Hero’s Weapon

The choice of weapons in a tale, especially a fantasy tale, has long been a way of signaling the personality and role of a character. The page “Weapon of Choice” on the TV Tropes website discusses this in great detail (and is certainly worth perusing). If you look at Hickman’s cover illustration depicting a statue of Glory Road’s three major protagonists, you’ll notice examples of this signaling to the reader: Oscar, the hero, is of course armed with a sword, the traditional heroic weapon. Star is armed with a bow, a weapon often used by female characters and associated with composure in dangerous situations. Rufo crouches while holding a spear, a weapon often used by supporting characters (which he is pretending to be for much of the narrative).

There is a long tradition of heroes from history, myth, and fiction naming their swords. Arthur carried Excalibur, Charlemagne wielded Joyeuse, Roland rode into battle with Durandal, Heimdall is the guardian of the mighty Hofud (also called Hofund, Hoved, etc.), Corwin of Amber brandished Grayswandir, the Gray Mouser had Scalpel while Fafhrd had Graywand, and you can’t swing a cat in Tolkien’s tales without hitting a sword with a name and lineage. Heinlein conveniently had his hero’s sword inscribed with a Latin phrase that serves as a theme for the novel, “Dum vivimus, vivamus,” or “while we live, let us live.” Oscar then gave his sword a gender and dubbed her “Lady Vivamus.”

The sword Heinlein chose was not the typical cross-hilted broadsword of European historical fantasy, but is instead described as:

A saber, I suppose, as the blade was faintly curved and razor sharp on the edge and sharp rather far back on the back. But it had a point as deadly as a rapier and the curve was not enough to keep it from being used for thrust and counter quite as well as chopping away meat-axe style. The guard was a bell curved back around the knuckles into a semi-basket, but cut away enough to permit full moulinet from any guard.

This description bears no small resemblance to a naval officer’s sword, which Heinlein would have carried for ceremonial purposes during his days at the Naval Academy in Annapolis. And in his era, officers were still trained in its use. The photo below is of my own sword from my days at the Coast Guard Academy, and you can see how it matches the description of Lady Vivamus in many respects.

Glory Road

The book is narrated in the first person by E. C. “Oscar” Gordon. He is presented as being in his early twenties, but while I bought that when I first read the book, as an older reader, I find the voice unconvincing. Oscar knows too much about too many things, and his frequent digressions on topics like taxes and marriage sound more like a man in his 50s (which Heinlein was when he wrote the book) than a baby boomer just coming to adulthood in the early 1960s.

After we’re given a mysterious hint of a world different than our own, we learn that Oscar is not in a good place, mentally speaking. The story begins with him telling his draft board to send him his notice, and soon he finds himself on the front lines of a conflict in Southeast Asia that is not quite a war yet (this being written in 1963, we can imagine it growing into the Vietnam War). The young man is a good fighter, but a cantankerous soldier, making corporal (at least seven times, in fact). As Oscar spins out his tale of woe, you begin to wonder when the adventure promised on the cover of the book is going to begin. In fact, if there is a single word that describes this book other than “adventure,” it would be “ennui”—“a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction arising from a lack of occupation or excitement.” Breaking down the 294 pages of the book, I discovered that it consists of 33 pages of Oscar complaining about his life, 31 pages of Oscar preparing for his quest, 143 pages of Oscar engaged in his heroic quest, and the rest describing Oscar dealing with the aftermath of the quest, again battling ennui, and discovering that “happily ever after” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. All adventure books have their share of non-adventure content, but this one has more than its share of curmudgeonly complaining.

What changes our hero’s attitude is his meeting with a beautiful and mysterious woman, who he calls Star, and who in turn gives him the nickname of Oscar. I was enchanted by Star in my youth, but as an older reader, I find both the physical descriptions and behavior of the character grating. Star is a richly imagined character, with agency in abundance. But she is described strictly from the perspective of an objectifying male gaze, and for a capable and powerful woman, she comes across as frequently submissive to Oscar. She and a mysterious older man called Rufo take Oscar to another world, Nevia, where firearms do not work. Rufo unfolds a backpack that is far bigger on the inside, containing an armory full of weapons, food, and a whole wardrobe of clothing. The first threat they face is an indestructible monster named Igli, who is defeated in a clever manner by Oscar. They then must face Blood Kites, climb down a 1,000-foot cliff to meet the vicious Horned Ghosts, and venture through an almost impassable swamp inhabited by creatures called the Cold Water Gang. This was my favorite part of the book, as we got exciting adventure, well told in a manner that made it feel immediate and real.

But then, in the midst of the narrative devoted to the quest, which already make up less than half the book, we get about forty pages devoted to sex. Not people having sex, just people talking about sex. Our intrepid adventurers arrive at the estate of the Doral, an old friend of Star’s, who treats them to an impressive banquet. And then, when everyone retires for the evening, Oscar is offered company by their host’s wife and two of his daughters, and refuses. This turns out to be a major snub in Nevian culture, almost gets them killed, and gives Heinlein an excuse to go on for pages and pages with his opinions on sex and relationships. And I will just say that, personally, the less I read about Heinlein’s thoughts on these issues, the better. That’s probably why of all his books, I like the juveniles the best. This passage ends with Oscar and Star deciding to marry, after which she behaves even more submissively.

With that out of the way, our heroes return to their quest, which involves battling fire-breathing dragons, with the mechanics of this ability being very well thought out. Our heroes then travel to yet another world, one where gravity, the atmosphere, and the nature of reality itself is unpleasantly different. They must make their way through a maze within a massive tower to retrieve the Egg of the Phoenix, the MacGuffin of their quest. The combat through the corridors of the tower becomes surreal in a way that is described very evocatively, and there is a masterfully described sword fight as Oscar meets what video gamers would call the final boss.

Then, at the point where most tales would end with the heroes living happily ever after, there are more than seventy pages to go before the story concludes. Oscar finds that the greater universe (or multiverse) is as grim and problematic as the situation he left behind on Earth. He has not been given the whole truth about the nature of his quest, and finds he has been manipulated at nearly every turn, even before he met Star. His wife turns out to be a kind of Empress, and not just a leader of worlds, but of a reality-spanning polity. And Oscar finds that being a retired hero, and consort of a powerful ruler, is not the most satisfying of roles. There ensues a lot of discussion about the meaning of life, the value of work, interpersonal relations, sex and gender roles, and more than a few heavy dollops of ennui, although Heinlein finds a way to end the book on a hopeful note.

Final Thoughts

As a youngster, I read Glory Road into tatters. There were parts I loved, and a few parts I didn’t, but I found all of it interesting at the time. As an older reader, there are still parts I love, but the other parts I find pedantic, and my overall impression of the book is definitely mixed. The adventure is still first-rate, and the book is a very convincing presentation of a portal fantasy that might feel insubstantial in other hands. But the lecturing on politics, and especially on sexual issues, is grating, and if I would recommend this book to a new and younger reader, I would do so with definite caveats. As a youngster, I didn’t mind authors preaching to me. But now that I am old enough to have formed my own opinions, I don’t need someone else trying to use fiction to force their philosophies on me in an overbearing manner.

I am sure a lot of you out there have read Glory Road, or other works by Heinlein, and have your own thoughts to share. I look forward to hearing them, but do ask you to keep the responses civil and constructive, and let’s keep our discussion focused on the book itself, rather than debating the merits of the author’s personal viewpoints.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I can’t remember when I first read this; probably junior high or high school. I absolutely loved it. But I haven’t read it since then and I suspect I’d have your reaction to it.

Wow, I didn’t even know that the author from Starship Troopers was so prolific! I need to go read his other books, Starship Troopers is one of the best sci-fi books I ever read.

I love your texts, I readed almost all of them and waits anxiously for the next one. You showed me that the fantasy/sci-fi genre is so diverse, because before I was just finding that I didn’t like the genre anymore, but your recomendations made me love the genre again! Thanks for the texts!

I haven’t read this for a good many years. I would have been in high school or college when I first read it, early to mid 1970s. I remember enjoying it. My husband and I make occasional jokes about Igli and about the backpack with a larger inside than outside (well before we met a Tardis). I also remember that I left the book sitting on a table at home and my father, an ex-Navy man who had never read any science fiction (he was a history buff and went for things like the Hornblower series) picked it up, found parts of it laugh-out-loud funny, and became a Heinlein fan.

I suspect I would not enjoy a reread very much but am tempted to try anyway.

This was one of my favorite books as a kid not just for the concept of “what happens after hero slays monster and marries princess?” but for the sly humor “‘Is that a yellow brick road?’ ‘Yes, that’s the color clay they have here.’ ‘Okay, I get it but don’t make a hobbit of it.'”

On recent re-read the behavior of Star, and more especially Oscar yelling at her when she disagrees with him until she meekly replies “yes, m’lord” was very disturbing and has not aged well since the 60’s. The explanation that she was trying to build up his ego and make him a hero doesn’t seem to make this any better.

This was my second favorite Heinlein book and I still have good memories but for a reread I now go to my favorite, “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.” And Wye Knott?

Glory Road is definitely not on my Heinlein re-read list. When I think about it now, about all I remember is the ennui and the sex issues. I’ve forgotten most, if not all of the adventure plot. I notice that the “possessive guy who learns better” plot appears as far back as For Us, The Living.

I do believe this is the only book I have ever read with an infodump about the Irish Sweepstakes.

I never thought Oscar was telling the story as it happened, but recollecting it many many years later, which makes the voice of a fifty-year-old man fitting.

Star always annoyed me with her manipulativeness, but I tried to forgive her because she’s a politician, after all. It’s what they do.

My copy from the sixties has not quite fallen apart, and I reread it regularly.

I reread this a while ago, and found the Suck Fairy had been at it. Though the idea of training in heroism remains interesting.

for a story about somebody reawakened to life from ennui/despair, I prefer Silverlock.

I prefer the Heinlein juveniles for the same reason you do!

Hmm… I don’t mind the scenes of Star “submitting” to Oscar all that much. It may appear that way on the surface, but we have to remember that she has been manipulating him from before they ever met. Also, Heinlein women almost always practice relationship judo where they get what they want and make it appear that it is the men’s idea.

On my last re-read though, I hated the stop in TexasNevia. I wish RAH had joined some nudist resorts and swingers clubs and worked out his issues in real life and not in his fiction. I generally support the idea of letting people sleep with who they want, but he has such a creepy, cringeworthy way of writing about it :(

It’s funny you should say that. RAH was a practicing nudist and attended several resorts. Also he (and at least one of his wives) did try their hand at swinging, as I recall.

@2 Thanks for your kind words.

@7 Silverlock. Now that’s a name I’ve not heard in a long time. There’s a book worth revisiting!

It’s been a long time since I’ve read this, as well; I’d completely forgotten (deliberately?) about the long discourse on sex.

I remember enjoying the adventure parts on multiple re-reads. The no-happliy-ever-after part I remember hating the first time I read it; on later reads, I remember appreciating the nuanced take and the message without enjoying the presentation. I suspect if I went back to read it today, I’d probably find that the ‘best’ (or at least best written) part, but still wouldn’t enjoy it.

@@@@@ 10. AlanBrown,

@@@@@7 Silverlock. Now that’s a name I’ve not heard in a long time. There’s a book worth revisiting!

A’s the abyss, and a man to the Devil

B is the great Beowulf, holding high revel

C is lithe Circe, without inhibitions

D is the Delian, ordainer of missions

E’s Euphenspiegel, a prankster and jiber

F is Fjoine, a royal imbiber

G’s des Grieux, made a cuckold by Lucius

H is Houynyhm, wise as Confucius

I is Innini, a dangerous trollop

J’s Friar John of the powerfull wallop

K’s Karenina, poor passionate Anna

L in Long River, as pleasing as manna

M is the Murgatroyds, desperatly haunted

N is fair Nimue, desperatly wanted

O is the Oracle, shaking and wailing

P is Promethius, whose liver is ailing

Q is Quixote, the champion of ladies

R’s Rhadamanthus, a justice in Hades

S is Semiramis, queenly but lusty

T is young Tamlane, whose lover is trusty

U is dark Usher, the site of the tower

V is Van Kortland, as bold as Glendower

W’s Watling Street, road of adventure

X is bright Xanadu, grand beyond censure

Y’s lady Yang, and enchantment while riding

Z’s mighty Zeus, and a mystic cow-hiding.

There is the alphabet, listing each letter

Yet not listing episodes, matching or better

Encountered by dozens, with Shandon as leader

But shared, even-Stephen, with you as the reader

For Silverlock tells of his marvelous journey

Through John Myers Myers, who has power of attorney

To pass it to you with the imprint of Ace;

At every good bookstore, six bits on the face.

[John Myers Myers, The Silverlock Alphabet, 1949]

Yup, RAH definitely was not a feminist, but he WAS funny and could be inciteful. In my opinion, his best adult novel remains “Double Star.” However, it is true that his YA books are simply stupendous and hilarious. The extraterrestial Princess of “Star Beast” who is keeping the human as a pet to everyone’s vast shock at the end is hysterical. And he so enjoyed getting up literally every social convention’s nose, as it were. So glad that Stranger still lives….with all its revelatory prods at the religots!

I read Glory Road as a teenager mostly because it featured in a book of art inspired by Heinlein, Bradbury and others. Though I didn’t think much of the story, and glossed over the soapbox exposition (I think?), it did encourage me to think of 1st person narratives as being written / told to the audience after-the-fact. There were a few books before and many since then that keep reaffirming this story P.O.V. of mine, so when characterizations like Easy Oscar’s middle-aged mindset seem to intrude, it’s because the main character / narrator is telling the story years later.

In all honest, when I read Children’s and YA lit, I always keep this attitude in order to suspend disbelief enough to read the story.

So, the article’s author didn’t mind being preached to as a kid but found the same expositions to be “forced” and “pedantic” as an adult. This attitude conforms nicely with the ossification of young men’s minds as they grow older. I started reading Heinlein when I was nine years old and my asthma medicine would keep me awake all night long after everyone else had retired. With little else to do and T.V. in those days “signing off” at midnight, reading was my principal time traversing activity. After assimilating all of the R.A.H. juveniles, I found “Glory Road” during one pubescent summer. I felt like I was reading soft porn and being initiated into some of life’s more carnal aspects. I returned to the story multiple times since then and found new and refreshing insights after each reread. As a product of his time, Heinlein tried on many different hats and writing styles. When he valiantly, in my opinion, wrote from the female perspective in stories like “Podkayne of Mars”, “Friday”, and the trans-gender “I Will Fear No Evil” I got the impression that he didn’t rely entirely on his own perspective but tried to include the point-of-view his wife Virginia offered. I always felt that Heinlein was ahead of the curve when it came to trends and concepts for new material to explore. I generally found his polemics to be thought-provoking rather than pedantic. His presumed chauvinism and militaristic attitudes were usually set-ups for opposing viewpoints that provided much of the dynamics for the plotlines that were foundational. I can’t think of a single case in which he didn’t afford his female characters respect and acknowledgment for their superior negotiating skills. A necessity when one party is operating from a position of physical inferiority. “Glory Road” was written to order for a boy entering manhood and, in my opinion, would make an incredible screenplay with all of the tropes and memes that are currently in fashion.

ISTR that E. C. (as he was then known) went from high school straight to college, then dropped out, making him (a) draftable and (b) ~20, rather than early 20’s — but I last reread this ~37 years ago, and memory may have faded. I do remember a colleague age 21 in 1972 finding Oscar unstomachable, so he wasn’t universally appreciated even by the young. ISTM that lectures had been popping up in RAH books for at least a decade; here they’re larger, although not as blatant as in later books. RAH does tell you before the story starts that it’s going to be about someone who had his mind opened (unless Baen chose to leave out the epigram from Caesar and Cleopatra).

BTW: somebody pointed out somewhere that the “final boss” is clearly Cyrano de Bergerac, although we’re given no explanation how he ended up on Hokesh.

@6: I don’t think the decades-later-retelling idea works; the last page is in the present tense and not long after Oscar returns to Earth. I think RAH just decided not to use Western Union.

@15: One person’s ossification is another’s realizing that much of the world has moved on from the year a book was written in.

It always takes me a moment to remember which one is Glory Road (Heinlein) and which one is Glory Lane (Alan Dean Foster). Both have fish out of water in a much bigger milieu but Foster’s is the one with a very capitalistic view of the universe, done in a humorous style that I can only describe as “almost, but not quite, entirely unlike Douglas Adams.”

The only thing I really remembered about the Heinlein book was AFTER the quest, when the hero realizes he’s a backwater bumpkin in that civilization, unble to find his place, and what he does about it (spoliers). Thank you for rereading this for me so I don’t have to do it again.

I used to be impressed that Star could chose her career over her marriage, but then I found out about Heinlein’s belief that women couldn’t combine working for money with marriage.

@13 I think many of the posters would agree with you about RAH being incite-ful. I enjoyed his midrange more than his juveniles but that may be because the first one I read was “Rocketship Galileo,” a book that caused me and my friends to run around shouting “NAZIS ON THE MOON!!!!!!”

@18 May I ask where you found out about that? That doesn’t sound like him to me. Was it a character that espoused that, or Heinlein himself?

Thanks,

@20: I’m not sure about career and (mere?) marriage, but the incompatibility of career and family is one of the drivers of Podkayne of Mars, as the RAH-figure (great-uncle Tom) vigorously tells her parents at the end of the story (just in case the reader hadn’t gotten the point long before).

That’s an all-time great typo (or a great pun).

@20: Discussions of the Patterson biography, which I admit I haven’t checked. The claim was that Heinlein forbade Ginny to work for money even when they were broke.

It does show up in some of his fiction– Podkayne and Glory Road, notably.

It’s a little different in Beyond This Horizon. Phyllis does go back to part-time work and it doesn’t seem to stress her marriage.

I don’t remember To Sail Beyond the Sunset well enough to say. Maureen set her hand to all sorts of things, but I don’t remember if it was while she was married. The marriage ended over her husband’s infidelity, so not related to working.

Oh, right, “The Menace from Earth”, where the viewpoint character assumes that she and her eventual husband will form an engineering partnership together. Does that count as a wife working for money? Did Heinlein’s views harden at some point? Or was he inconsistent in his fiction?

“The Menace from Earth” came out in 1957, when he was already starting to get cranky; maybe he wasn’t as fixed as when he wrote Podkayne (5 years later), or maybe he thought that Holly, being just 15, had time to come to her senses — or that after she was married she’d just do the parts Jeff felt she had time for. Beyond This Horizon was earlier (1948), so he may have been more flexible, or figured that much “work” was more like a hobby — the economics in that book are strange.

I enjoyed Glory Road, but it seemed to me to be the “missing link” between the wonderful early Heinlein who wrote Starship Troopers and Space Cadet, and the unreadable later Heinlein who wrote Number of the Beast. It has the male characters pontificating endlessly on life, the universe and everything, while the author seemingly looks on approvingly and the female characters don’t dare to disagree, but with enough actual action and adventure to make it all worthwhile.

(I should add that I have no idea in what order Heinlein actually wrote his books, just the impression I got from the order in which I came across them in the library.)

Glory Road certainly wasn’t the worst thing RAH ever wrote (Farnham’s Freehold…) but it’s probably in the bottom 5. Definitely a “read once”.

One thing we’ve seen here in the US during the pandemic is a lot of women forced out of the workforce to take care of children. He seemed to think that was a matter of biology rather than society though

What I took away from Podkayne, when I read it in my teens, was that liking girl stuff, like boys and babies, didn’t make you an airhead and there are alternatives to beating your head against a glass ceiling to getting where you want to be.

Many of Heinlein’s juveniles speak of the prejudice against women in technical fields and all emphasize how blatantly unfair it is. Poddy reconsiders her ambition to be a pilot commander because she knows the odds are stacked against her. She never believes that prejudice justified. Hazel Meade Stone quite her job in engineering after being repeatedly passed over for promotion because she was a woman. Her granddaughter Meade could get a job as an astrogator if the space lines weren’t prejudice against women. And Holly has absolutely no intention of giving up her career as a spaceship designer and there’s not the slightest suggestion that she should.

As for Star, she’s empress of 20 universes and has huge amounts of power. If she defers to Oscar it’s because he’s in the right or she’s manipulating him. Oscar comes to realize she’s been manipulating him their entire relationship but he accepts it because it’s never been against his own best interests and he doesn’t expect to rank above the multiverse in her priorities.

NancyLebovitz

I don’t remember To Sail Beyond the Sunset well enough to say. Maureen set her hand to all sorts of things, but I don’t remember if it was while she was married. The marriage ended over her husband’s infidelity, so not related to working.

Maureen worked as office manager, secretary, and bookkeeper for their geology business. She held things together while Brian was in the field. She ran everything while Brian was off to war.